So, you have applied the computer file method in part 1 and generated many sci-fi concepts. This is a good moment to go from creative liberation to critical thinking. Evaluate your concepts one by one and select your favourite one. Which one drives your curiosity enough to stay with it and write a short or long story based on it? If you’re writing a movie, which concept would be more visual or feasible to film? Think about it and then choose the one that feels best.

Do you have it? Good. Now, there are many ways to improve and develop this concept. Let’s get to it.

Refining Your Idea with Scientific Principles

You don’t need to study science to write science fiction. You don’t even need to keep up with science’s latest developments. However, I do believe that some key scientific principles will help you move your story forward immensely.

Among the many principles that populate science, I’ve selected three that have been of great help during my sci-fi writing.

1. Scale

Everything in science is related to scale. In physics, the largest scale is dominated by general relativity, and the smallest scale is quantum mechanics territory. The physical laws and typical behaviours are different in these two extremes, and so are stories when you play with the size of your concept.

For example, we are all familiar with the concept of body-swapping. Person 1’s mind goes into Person 2’s body, and vice versa. It’s been done many times with two people. There’s an episode of Futurama in which the swap happens between a few more characters, and that adds a bit more complexity.

But what if everyone swapped bodies with everyone at the same time? Imagine a global rotation of minds. Now the personal problem becomes a societal one. Soldiers aren’t soldiers, politicians aren’t politicians, and the whole world descends into chaos. This is the concept of my next novel, Second-Hand Bodies. I fell in love with the idea from the beginning, and, as you can see, all I did was to take the existing concept of body-swapping and change its scale.

So go ahead and take your sci-fi concept to the biggest scale possible, then to the smallest scale possible. Did you find anything interesting there?

2. Playing with opposites

Opposites are omnipresent in science. There are positive and negative numbers, positive and negative electric charges, high and low temperatures, matter and antimatter, and so on. This can be an entertaining way to spice up your sci-fi concept.

For example, I was long obsessed with the idea of the Antivampire, a person who mutates into a creature that everyone wants to eat. This isn’t a particularly new idea (see The Perfume, for example), but I haven’t heard of anyone giving it this name. The real moment of inspiration came when I thought of keeping the entire food chain in the story: vampires-humans-antivampires, and then having the antivampires eat the vampires, making it a circular food chain, like a rock-paper-scissors mechanism. So now, we have three species in a similar position, joining enemies to fight other enemies. That’s the premise of Blue Nails, one of the stories in Broken Horizons.

3. Generalisation

The word generalisation is often used in everyday life, but the scientific concept behind it might be tricky to apprehend for someone who hasn’t studied science. In short, generalising means giving all measurable quantities involved every possible value. I’ll try to illustrate this with time travel stories.

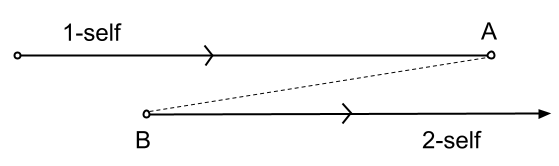

Let’s imagine that a person is living his life and suddenly travels a few days into the past. I’ll assume for now that this person is separate from his past incarnation. In other words, he’s in a different body (2-self) from his past self (1-self). The timeline would look like this.

The top line represents the first timeline of the person (1-self, the person before travelling back in time), and then it jumps to the second timeline (2-self, the same person after travelling back in time). In this case, 1-self and 2-self could interact with each other between times B and A.

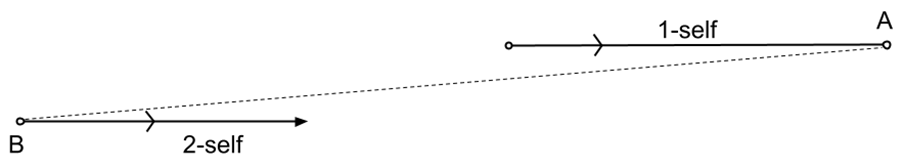

What if the person travels in time again, but before they were born? Well, it’d look like this.

In this case, the 1-self and 2-self don’t interact directly, but it’s up to the writer to decide if 2-self can change the future of 1-self.

If you’re writing a time travel film, draw many of these diagrams. I’m not only suggesting you make one character go back in time several times, I’m suggesting you mix time diagrams for different people, that you cut and paste the timelines without any regard for realism or understandability—those two things can come later. Think outside the box, inside the box, and outside the box of the box. Leave no option unexplored and choose your favourite. Generalise time travel as well as you can.

Next Step: Extending Your Concept through Interconnection

Everything in the Universe is connected with everything else, and I don’t mean spiritually but scientifically. Moving one tiny particle leads to changes in its surroundings and might end up taking the world in a whole different direction. If you’re familiar with scientific formulas, you know that one quantity is a function of many others. The same happens in science fiction.

When you introduce your little variation in the world, it’s going to affect not only the main plot and the characters in your story, but probably many other aspects of society. Doing the diligent work of figuring out the consequences of your concept is key to creating a solid sci-fi world.

For example, we’ve all lived through the COVID pandemic and are familiar with its consequences: hospitals running out of beds, restrictions in mobility, lockdowns, etc. Now, for one of my stories in Broken Horizons, I chose a pandemic where people had to stay six feet apart or closer to survive. They need at least one person within their six-foot radius or they will pass away. I hope this never happens in real life, but within the story, I needed to be logical and realistic with its consequences.

First of all, many people will die at once. If the pandemic strikes while people are sleeping in Europe, you can assume most of the single people living there will die, unless they’re having a one-night stand or they’re sharing a bed with someone else. Couples will only survive if someone warns them about the problem before one of them goes to the bathroom. Solitude will become precious, so some rich people might pay a lot of money to spend time with people in a coma, just so they can feel truly alone. I ran many scenarios in my head and followed logic to build my world. I kept using my imagination within the plot, but I always had to keep the interconnection between all elements in check.

Almost there!

If you’ve found a concept you like with the computer-file method, refined it with scientific principles, and thought about the interconnected elements in the plot, you’ve done a lot for your world-building. At this point, I tend to go wild and brainstorm about my story, so I find the plot and the characters within the world I’ve created.

From here on, there are many methods to proceed. If you are more on the planning side, you may figure out many plot and character elements before putting pen to paper. If you are more on the pantser side, you could start writing straight away.

How about you? What are the steps you follow to write sci-fi? Is there anything you miss in the article? Let me know in the comments!

Un comentario en “Generating Sci-Fi Concepts. Part 2 – Refine and Extend”